On a very irregular basis, Sonic Asymmetry will devote a posting to a review of an entire series of recordings of historical significance. This time, a chunk of cyberspace goes to Henry Cow’s elusive, unofficial documents.

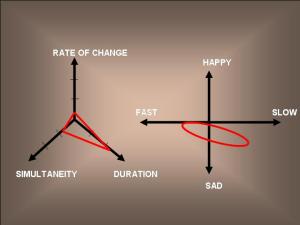

Looking back in history, one can identify several tipping points that durably changed the nature of musical creation. Those who operated at these inflection points not only enriched musical imagery and hugely expanded future artists’ perceptual map. They also influenced the audiences’ musical memory and, as a consequence, created an entirely new set of auditory expectations. Pierre Schaeffer’s 1948 lectures played such a role in concrète and electronic music, privileging radical changes in aural perception. Ornette Coleman’s collective improvisation, immortalized in December 1960 had the most potent impact on human capacity to capture the power of spontaneous intersubjectivity. In the process, Coleman pushed the jazz world into cognitive dissonance for at least five years.

In the broadly-defined rock format, such a tipping point was reached when several British musicians coalesced their revolutionary visions into the extraordinary story of Henry Cow.

By the time the band surfaced with official recordings, the musical axial age (1968-72) was already over. But the uniquely creative atmosphere that prevailed during those years undoubtedly planted the seeds that eventually generated some of the most consistently refreshing archives of musical creativity – both composed and improvised. Zürich’s Rec Rec Katalog stated in the mid-1980s: “Mit einer unglaublich radikalen Konsequenz zeigten sie uns, wie die künstlich gestzten Grenzen in der Musik durchbrochen warden können – und sie gingen mit diesem Bewusstsein bis zum Extrem. Ihre Musik ist auch heute noch hörenswert und bestitzt für die Entwicklung der progresiven englischen Musikszene exemplarsichen Wert“. Over twenty years later, nothing has happened to invalidate these opinions.

This year we celebrate 30 years since Henry Cow disbanded and 40 years since the group’s creation. It is an excellent opportunity to review the less-known, unofficial recordings of the band. In order to avoid lengthy repetitions, I first list the full names of musicians who, in various periods, appeared as more or less ‘official’ members of Henry Cow:

· Tim Hodgkinson – organ, alto saxophone, clarinet, piano, prepared piano, electric piano, Hawaiian guitar, percussion, vocal

· Fred Frith – guitar, violin, viola, xylophone, piano, bass, vocal

· Andy Spooner – harmonica

· Rob Two – guitar

· Joss Grahame – bass

· Dave Atwood – drums

· Andy Powell – bass

· John Greaves – bass, piano, celeste, whistle, vocal

· Martin Ditcham – drums

· Chris Cutler – drums, percussion, radio, objects, toys, whistle, noise, trumpet, vocal

· Geoff Leigh – tenor and soprano saxophones, flute, clarinet, recorder, vocal

· Lindsay Cooper – bassoon, oboe, recorders, flute, soprano saxophone

· Dagmar Krause – vocal

· Peter Blegvad – guitar, clarinet, vocal

· Anthony Moore – piano, tapes, electronics

· Georgie Born – bass, cello

· Annie-Marie Roelofs – trombone, violin

~~~

“Early Demo Tapes 1973”*****

This collection includes a number of tracks from the period immediately preceding the first LP “Leg End”. The official album was recorded between May and June 1973, so it is probable that the titles on “Early Demo Tapes” were immortalized during the second quarter of that year. The line-up is the same as on the first LP (Leigh/Frith/Cutler/Hodgkinson/Greaves). The material includes three tracks from “Leg End” (“Nine Funerals for the Citizen King” appears in two different versions), as well as a nine minute long “Hold to the Zero Burn” and a short “Poglith?”, neither of which appears on official issues.

The presence of the former track is confusing and I can barely find any similarity between this version and the only studio document of this composition – presented on Tim Hodgkinson’s CD “Each in Our Own Thoughts” (1994). In the liner notes, Hodgkinson mentioned that it had been commonly played by Henry Cow live in 1976-77. However, the material on “Early Demo Tapes” would mean that “Hold to the Zero Burn”, at least in its skeletal form, is much older than indicated by Hogdkinson. If it is so, its vintage form it is much less extended (9 minutes instead of 16 minutes on “Each in Our Own Thoughts”) and lacks the lengthy intro.

The sound quality on this bootleg is good.

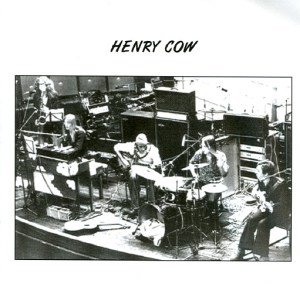

“Henry Cow & Co.”******

This is one of the most interesting of these collections, even though it incorporates some tracks that are not nominally “Henry Cow”. Three of the group’s compositions were recorded in the BBC on 24 April 1973. This set includes the excellent “Guider Tells of Silent Airborne Machine”, which has not been released anywhere else. The session also incorporates yet another version of “Nine Funerals for the Citizen King” and “Bee”, both known from LP “Leg End”. The line-up is Frith/Hodgkinson/Leigh/Cutler/Greaves.

This is followed by a medley, opening with hitherto unknown “Pidgeons”. This is an exploration in Lol Coxhill or Scratch Orchestra-style, followed by two tracks from the side A of LP “Unrest”, but sequenced in a reverse order. On this recording Henry Cow are Frith/Hodgkinson/Cooper/Greaves/Cutler. It was documented on 25 April 1974, i.e. a month after the “Unrest” sessions were finalized. The recording venue also appears different. “Unrest” was recorded at Manor Studio, whereas the April session was taped at Langham Studio 1.

There are 10 other tracks included on this bootleg and they are all tangentially related to the history of Henry Cow. Five of them are signed by Fred Frith in an unusual trio with Anthony Moore and Dagmar Krause, recorded on 2 December 1974. Three excellent pieces are by John Greaves and Peter Blegvad, who are accompanied here by Anthony Moore, Tom Newman and Andy Ward (13 December 1977). This is far superior to any other Greaves-Blegvad bootlegs I heard from the era.

And finally, an expanded Slapp Happy adds two cuts from 25 June 1974. The usual trio of Moore-Blegvad-Krause is augmented here by Frith, Cooper, Leigh as well as Robert Wyatt and Jeff Clyne. This is an unusual opportunity to hear Lindsay Cooper and Geoff Leigh together (the only others being “War” from November 1974, which opens LP “In Praise of Learning” and two tracks on “Desperate Straights” realized around the same time). To the best of my knowledge, this is not the material which was destined to become Slapp Happy’s “Europa” single and John Greaves does not appear here. The two tracks are “War is Energy Enslaved” and “Little Something”. The latter had previously surfaced on Robert Wyatt’s collection of rarities entitled “Flotsam Jetsam”

The sound quality on this collection is superb.

“Rare Tracks Compilation”*****

The unimaginatively entitled “Rare Tracks Compilation” collects several sessions, apparently from 1974, immortalized courtesy John Peel’s Top Gear. Snippets from the same session as above (25 April 1974) are also reproduced here. Although the line-up is not mentioned, we can assume that it is no different from the “Unrest” quintet.

The set begins with a 14-minute track of appalling sound quality with different versions of tracks from “Unrest”. This is followed by 59 seconds hijacked form LP “Miniatures” – Dagmar Krause’s sampled voice from an Art Bears track and skittery improvisation.

It is worth acquiring this disc for the next four sections, none of which I am able to disambiguate in full. First we have an excellent 3 minute interplay with saxophone to the fore and a spasmodic electric piano in tortured tremolos and clusters. The texture of this track and Geoff Leigh’s presence indicates that this is Henry Cow circa 1973, and not 1974 as stated on the cover. What follows is a six-minute piccolo call, shadowed by some wailing, manic voices. Many improvisations from around 1976 used this formula for an initial take-off, and there is a female voice here, but not Dagmar. In addition, the saxophone is again very prominent, and this type of Frith’s fuzz was unheard after 1974. This is followed by a 5-minute long abstract extemporization in a colorful, string-based style as known from LP “Greasy Truckers”. Since that 21-minute contribution was recorded in November 1973, I stick to my conviction that the material presented here was also taped around the same period. The next track is 6-minutes of deep, ominous piano clusters, soprano saxophone squeals, Cutler’s scraping and Dagmar Krause’s dramatic singing. This slab of sonic menace is probably from around 1976. It is as close to contemporary music as Henry Cow would ever get. Years later Tetsuo Furudate and Zbigniew Karkowski would follow that path.

These four sections – which clearly justify the purchase of “Rare Tracks” – have a sound quality ranging from very good to superb.

Unnecessarily, someone decided to fill up the remaining disc space with material which is neither rare, not stylistically compatible with what we have just heard. First we get “Viva Pa Ubu” and “Slice”, as known from LP “Recommended Records Sampler” (1978), then a number of Art Bears’ and the Work’s songs lifted from their official singles. Finally, there are Fred Frith’s improvised guitar-based numbers with Dagmar Krause. This is the same material as on “Henry Cow & Co.”.

“In the Name of Freedom”****

The collection of live recording from the 1975 tournée has been issued under the name of ‘Henry Cow featuring Robert Wyatt’ and showcases Henry Cow as a septet of Krause/Cooper/Frith/Greaves/Cutler/Hodgkinson/Wyatt. Were it not for the less-than-perfect quality of the recordings, the triple CD collection could constitute a welcome complement to the legendary double LP “Concerts”. The official album featured live recordings collected between September 1974 and October 1975. This unofficial set concentrates on the concerts performed in May and June 1975. Much of the material is similar to the official “Concerts”, but it predates the groundbreaking medley of themes that were included on side A of the double LP. Indeed, “Concerts” were a misnomer – the breathtaking string of complexity on side A (“Beautiful as the Moon… Terrible as the Army with Banners”) was actually recorded in BBC Studios in August 1975. The bootleg brings two other versions of this uninterrupted sequence – one from a concert in New London Theatre (21 May 1975) and one from the photographically documented gig at Piazza Navona in Rome (27 June 1975).

But both concerts add another medley of themes, unknown from Henry Cow’s official recordings, entitled “Muddy Mouse(s)” and subdivided into five movements: “Solar Flares”, “Muddy Mouse(b)”, “5 Black Notes and 1 White Note”, “Muddy Mouse(c)” and “Muddy Mouth”. These are nothing more than concert versions of songs from Robert Wyatt’s LP “Ruth is Stranger than Richard”, where they appeared on side B. This material was salvaged by Wyatt from a failed collaboration with Frith. Frith was not happy with his own contribution to the project, but Wyatt went ahead and published it on “Ruth” – a record he was never fully satisfied with. The main difference between the LP version and the Henry Cow’s live rendition is the presence of Lindsay Cooper on gnarly bassoon instead of Gary Windo’s bass clarinet.

The three concerts (the third one being from Paris – Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, 8 May 1975) also replicate side B of LP “Concerts” with “Bad Alchemy” and “Little Red Riding Hood Hits the Road”. However, “Ruins” is attached here to the suite “Beautiful as the Moon…”. The London and Paris concerts also include long improvisations (11 minute each), which are unique. The interplay achieved on the Paris version is particularly impressive.

The lengthy collection ends, unexpectedly, with Kevin Ayers’s “We Did It Again”, known from Soft Machine’s first LP. This (only) version was recorded during the encore at the Paris concert. Apparently the band had not rehearsed this before. If that is true, they pull it off impressively.

“Ruins”****

This double CD comprises one disc with exactly the same material as “Early Demos” described above and one disc with the recordings made 26 March 1976 for Jazz Workshop at Nord Deutscher Rundfunk (NDR) in Hamburg. NB, the same material is also available on another bootleg simply entitled “NDR”. It presents yet another version of the “Beautiful As the Moon…” suite, complete with “Ruins”, but with a distinctively novel keyboard work. The line-up is the sextet of Frith/Hodgkinson/Greaves/Cutler/Cooper/Krause.

This live in studio document is, apparently, the last occasion to hear John Greaves with the band, as he officially had left the band on 13 March to work with Peter Blegvad on “Kew Rhone” (recorded in New York in October 1976).

The sound quality is very good.

“Kaleidoscope”****

Two lengthy improvisations (44 and 47 minutes, respectively) were recorded during the tour on 26 May 1976 in Trondheim, Norway. Henry Cow apparently played there as a quartet of Frith/Cutler/Hodgkinson/Cooper. The material is very interesting and unique, with a particular focus on acoustic piano parts and lengthy openings with flutes and piccolos. Unfortunately, the sound quality is acceptable at best.

“Unknown Session”******

This is a collection of recordings made apparently during the same Scandinavian tour in May 1976. According to the description, the band, captured live in Stockholm and Göteborg appeared as a sextet (Krause/Frith/Cutler/Hodgkinson/Born/Cooper). There are some doubts concerning this line-up. First, it is surprising to find here Dagmar Krause in such a magnificent form – most historians point to her absence from the tour. Still, she clearly is present. These would also be the earliest known recordings with Georgie Born on bass, if she really is present (?). It is known that during the auditions she edged formidable competition from Uli Trepte and Steve Beresford. However, I would be very surprised if she did, in fact, manage to join this tour, as purported by the description.

There are seven lengthy compositions here, one of which spans over 20 minutes. They are radically different and more evolved than the better known fruits of the 1975 concerts. Only on two of them can I detect familiar themes. It also includes some of the most unusually psychedelic guitar playing from Frith. The sound quality is very good.

The material also includes the anthemic folk song “No More Songs”, until recently undocumented elsewhere.

“Live in Paris, November 1977”****

Spanning two CDs, this live recording is important for being a rare opportunity to ascertain the validity of claims and counterclaims about The Orckestra – the collaboration of Henry Cow with Mike Westbrook’s Brass Band and vocalist Frankie Armstrong. The document stems from a concert taped on 20 November 1977 at Fête du Nouveau Populaire in Paris, eight months since the beginning of this ambitious collaboration. In addition to the sextet of Cooper/Cutler/Frith/Krause/Hodgkinson/Born, we have here Mike Westbrook (piano, euphonium), Dave Chambers (soprano and tenor saxophones), Kate Barnard (piccolo, tenor horn), Paul Rutherford (trombone and euphonium), Phil Minton (trumpet) and Frankie Armstrong (vocal). Again, Dagmar Krause’s participation is surprising, given that she had officially “left” Henry Cow a month before.

There are all together 11 tracks. The music is fanfaric, uplifting and quite distinct from Henry Cow’s other material, relying predominantly on Westbrook’s compositional framework. It is most rewarding when brass sections surge from impressionistic landscapes, prodding the entire ensemble into transformative activity that marries New Orleans marching band and lateral group improvisation. If you are able to imagine Music Liberation Orchestra overlaying “Nirvana for Mice”, “Ruins” or “Beautiful as the Moon” you are close. The brass section acts as a powerful enhancer, interspersed with Phil Minton’s or Paul Rutherford’s lyrical solos. On the other hand, Frankie Armstrong’s black singing seems a little out of step with the rest of the Orckestra. In the second half of the concert, the band also performs excerpts from Kurt Weill’s “Dreigroschen Opera”. Both Born and Cooper would continue to collaborate with Westbrook in future.

Unfortunately, the sound quality ranges from poor to acceptable, at best. It prevents us from adequately judging how sonically successful this notorious project was.

“Industry”****

This is Henry Cow with one foot in the grave, most likely stripped down to a quartet of Frith/Cutler/Hodgkinson/Cooper. The recording was made in the Spring of 1978 in London, probably some time between its unfortunate tour of Spain (with Phil Minton) and the last series of concerts in France and Italy. In other words, this is Henry Cow shortly after the official birth of Rock In Opposition movement (12 March 1978), which the band and Nick Hobbs championed. The material encompasses three improvisations (21 minutes, 12 minutes and 8 minutes), as well as “Slice”, “Ruins”, material from the then upcoming LP “Western Culture” (“Industry” and “Look Back”). Here again, the same “Recommended Records Sampler” versions of “Slice” and “Viva Pa Ubu” appear as a questionable bonus material.

The unique improvisations capture Hodgkinson in an almost Middle Eastern mode on clarinet. There is also a self-declared “Unreleased Number”, which is in fact an early version of Fred Frith’s “Time and a Half”, which eventually crept onto vinyl when Curlew recorded it in 1983-84 (LP “North America”).

The sound quality ranges from poor to acceptable.

“Culture de l’Ouest”***

A double CD with recordings made in Lyon, France on 6 June 1978. Most of the material is known from other versions etched onto vinyl either in January of that year, or over the following two months (July-August) at Sunrise Studio in Switzerland and published on LP “Western Culture”. However, in addition to “On the Raft”, “Falling Away” and “Industry”, we are served here with one unique improvisation and hitherto unknown live versions of “Viva Pa Ubu” and “Slice”.

The line-up here is Frith/Cutler/Hodgkinson/Cooper/Roelofs, augmented by a special guest – a pre-“Outside Pleasure” Henry Kaiser on guitar. It is unclear who plays the booming bass part. It does not seem to be Frith, unless Kaiser impersonates his style to perfection. It could be Lindsay Cooper on “air bass”, or it could be Kaiser himself. The poor sound quality makes it impossible tell.

It is known that Yoshk’o Seffer also performed with Henry Cow around that time, but so far I have not found any of these recordings.

As a (superfluous) bonus, the second disc adds (again!) the original studio recordings of “Slice” and “Viva Pa Ubu” from “Recommended Record Sampler”. We know that Georgie Born participated on one of these cuts, before her eventual departure in January 1978.

***

When in the early 1990s the first CD reissues surfaced in the market, several bonuses were squeezed at the end of the original material, distracting rather than supplementing the wholeness that these deservedly legendary recordings constituted. It was always hoped that they would reappear in full glory on a separate disc.

A long-awaited 9CD box of archival recordings and a 80-minute DVD are now expected to appear sometime this year to celebrate 40 years since Fred Frith and Tim Hodgkinson first thrashed it out in a noisy collaboration (apparently opening for a Pink Floyd concert). Chris Cutler et al have seriously stretched the patience of fans who waited so long for the official versions of Henry Cow’s historic recordings. But patience will be rewarded. Apparently Bob Drake did a great job cleaning the archives.

According to some previews available online, the commemorative boxes will contain elements of the material included on the above-mentioned bootlegs “Ruins” and “Kaleidoscope”. This is the perfect time to dream, and in this ideal dreamworld, my own wishes would incorporate the following historical sessions/concerts:

- Any material of the early trio of Frith, Hodgkinson and Andy Powell (bass). Powell is sometimes credited with exposing the founders to composer Roger Smalley’s ideas of extended composition (1970).

- Any material left over by Chris Cutler and Dave Stewart’s Ottawa Company, in particular their “Study for Keyboards” and Zappa pastiches (1971)

- Any material from Robert Walker’s production of Euripides’s “The Bacchae” (1972)

- Any material from John Chadwick’s production of Shakespeare’s “The Tempest” (1973)

- Any good quality version of “Hold to the Zero Burn” from the late 1970s.

- Professional quality recordings of the Orckestra (1977)

Robert Wyatt once famously quipped that Henry Cow were “the best band in the world”. There are many things in the world that separate my own Weltanschauung from Wyatt’s. But I do agree with him on this particular superlative. This judgment has survived too many years unchallenged to be dismissed any time soon.

Recorded 2004

Recorded 2004